By Robert D. Cunningham:

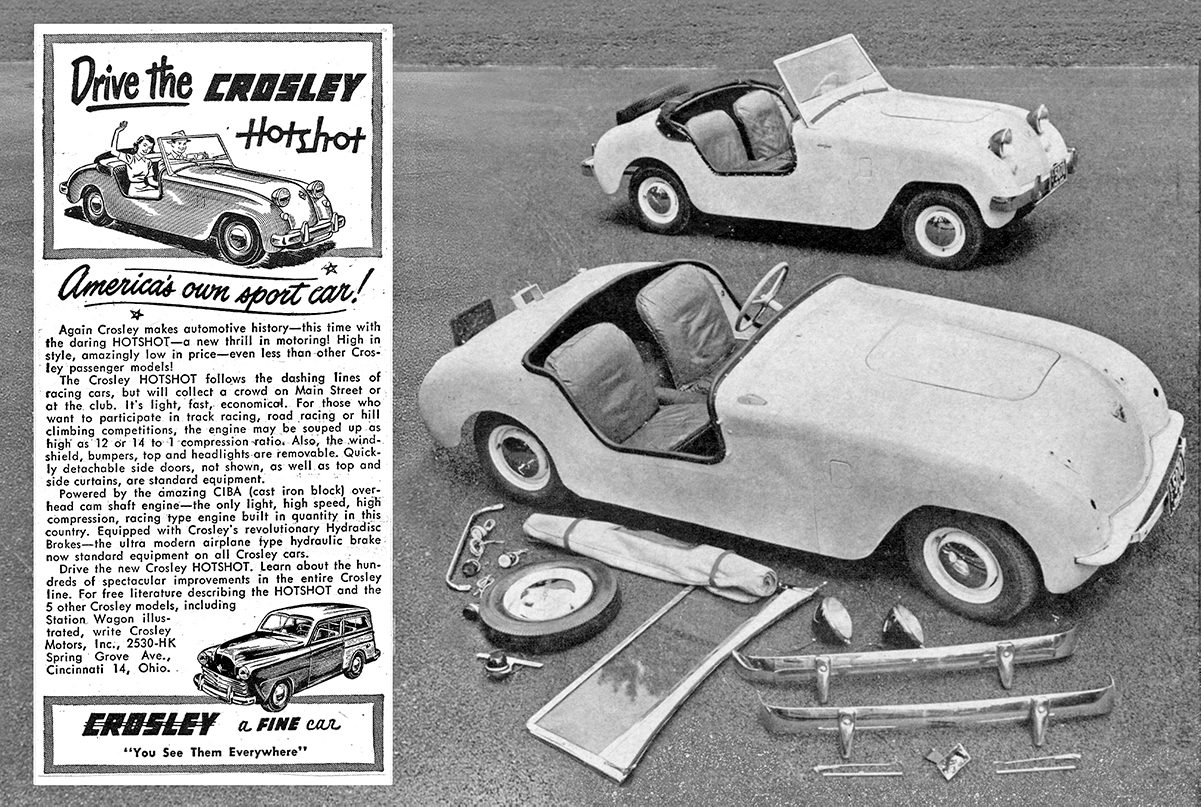

Powel Crosley, Jr. introduced his two-cylinder roller skate of a car in 1939, followed by slightly larger postwar offerings in 1946. All body styles were strictly practical until he unveiled his exciting new Hotshot on July 13, 1949. “America’s first true postwar sports car” was a bare-bones street racer. Being equipped with few frills allowed dealers to deliver the roadster for as little as $316 down and $7.64 per week, and at only $849, the Hotshot was the least expensive production car in America that year.

Lead Image – A California Crosley driver proudly displays a tiny loving cup won at the wheel of his four-cylinder 1950 Hotshot. The six exhaust ports were likely aftermarket fakes.

It was designed by Sundberg & Ferar to meet Powel Crosley’s specifications, and Crosley had Lincoln Zephyr stylist John Tjaarda layout the dashboard, which was not used on the production car. Depending on one’s economic background, the roadster was either a little racer or a big roller skate. It ended up being only 37 inches at the rear of the cowl and has seven inches of clearance. Easily stripped of windshield, bumpers, lights, spare tire, and other unnecessary items, the Hotshot, in racing form, weighed in at just 991 pounds.

Stock 1949 hotshot was easily stripped of extraneous do-dads to create a potent, lightweight racer for under $1,000.

The roadster body was fabricated from six basic panels welded together that form a sturdy body shell. It may have been the first production sports car to eliminate the grille, and cooling air was ducted to the radiator by an air scoop mounted under the front bumper. There were no hinged panels, such as doors, trunk lid, or hood. The 26.5 horsepower engine was accessible only by unlocking and lifting off a small, rectangular cover in the center of the front deck. It was an appealing package with styling similar to the bug-eyed Austin Healey Sprite, built a decade later.

The exciting new Hotshot attracted attention at local race tracks. Its unique suspension system consisted of conventional semi-elliptic springs up front and a torque tube located rear axle with coil springs on top of single leaves at the rear, providing a soft but stable ride. With increased compression and special 10:1 pistons, the pussycat Crosley became a tiger with top speeds approaching 85 miles per hour. Aftermarket parts supplier Mick Brajevich supplied Crosley owners with cast aluminum finned cam covers and oil pans, dual carb manifolds, headers, and other lightweight add-ons that could nearly double the horsepower and raise the top speed to 100 miles per hour. Fritz Feierabend drove car #2 to victory in the 1950 Grand Prix de la Suisse Occidentale for sports cars up to 750cc displacement. Despite the necessity for slowing down to navigate dangerous road curves, Feierabend averaged 51 mph. Oviedo Bernasconi’s Hotshot, which used an Ital-Mechanica compressor, placed second.

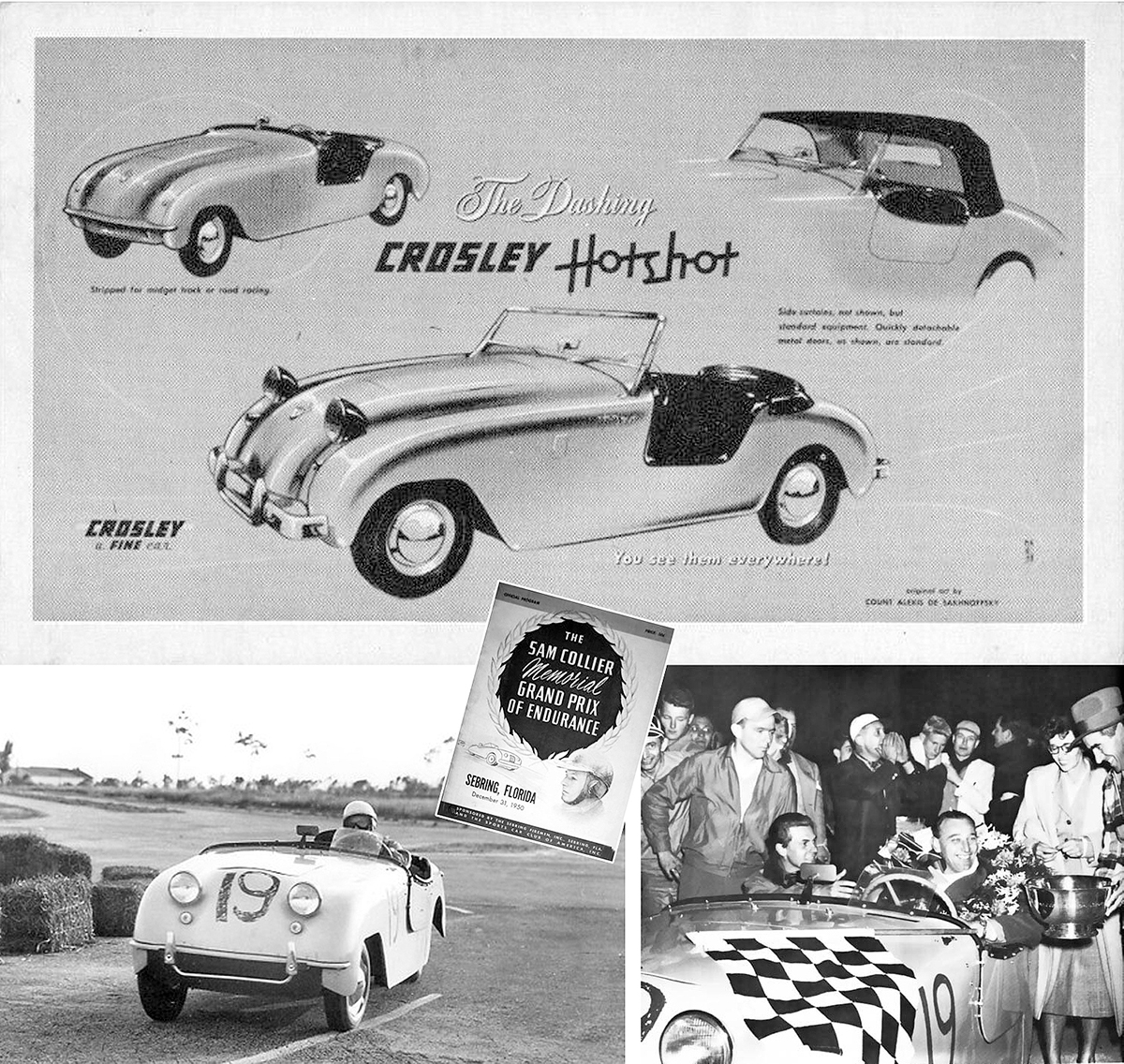

Later that year, on New Year’s Eve, drivers Fritz Koster and Ralph Deshon drove a Hotshot to victory in a six-hour handicapped road race, the first-ever held at the Sebring, Florida, airport. The Crosley’s participation was a snap decision. When Vic Sharpe arrived from Tampa in his Hotshot to deliver tires for Tommy Cole’s Cadillac-powered Allard, Sports Car Club of America members Koster and Deshon realized that the Crosley’s small engine displacement could be a real advantage. The event was run under rules devised by France’s Automobile Club de l’Quest, organizers of the famous Le Mans Grand Prix d’endurance. Winners would be determined only after applying a horsepower-to-distance mathematical formula, thereby making the contest fair to every participant, regardless of how much money they spent on development. Koster and Deshon quickly convinced Sharpe to loan them his car. Immediately they removed the hubcaps and windshield, bolted a short piece of Plexiglas on the edge of the cowl, and registered for the race.

A bone stock Crosley Hotshot rolled from the street to the track, and on to Victory Lane in the inaugural Sebring endurance event in 1950.

When the starter’s whistle blew, Koster and Deshon ran across the track with the other drivers and slid into the cockpit. Twenty-eight engines roared to life, and the race was underway. Koster quickly shifted the tiny transmission into high gear and kept it there throughout the race. Running at a constant 7,500 rpm, the Hotshot screamed like a chain saw on the straightaways and was driven wildly into the corners. In the end, a Ferrari logged the highest distance, having lapped the 3.5-mile course 166 times. The Crosley completed just 89 laps. However, after applying the handicapping formula, the only American car to compete emerged in the first place. Koster and Deshon rolled into the winner’s circle to receive a floral laurel, trophy, and accolades from seasoned racers.

Meanwhile, nonparticipant Phil Stiles periodically lapped the track to remove debris, including parts that had vibrated loose from the race cars. He was impressed by how well the winning Crosley held together, and his wife urged him to ask Powel Crosley to build a true racer for Styles to drive in the French Le Mans. Crosley liked the idea and engaged Floyd “Pop” Dreyer in Indianapolis to create a sleek, slender, fat-fendered racer.

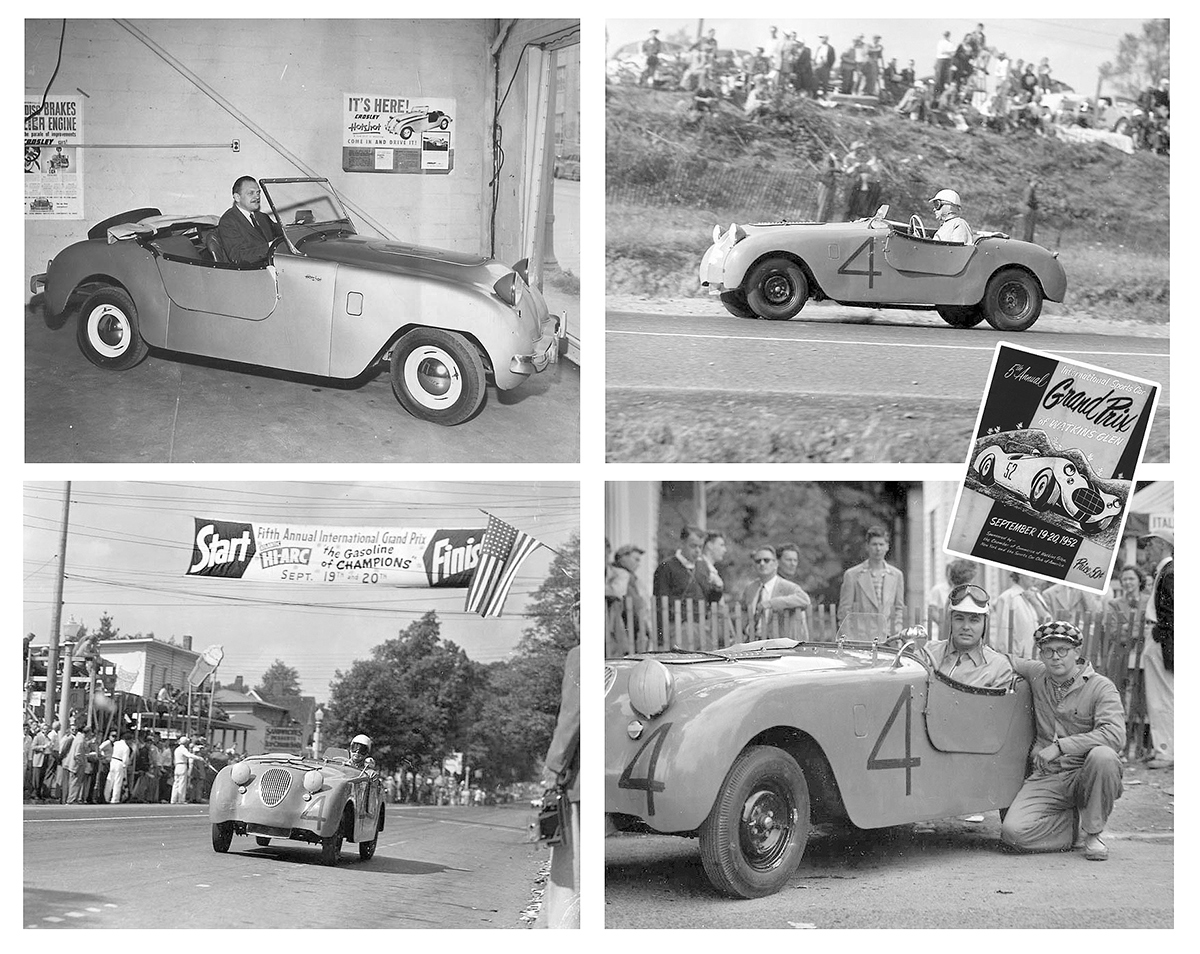

Dolph Vilardi drove a yellow 1950 Hotshot #4 with optional detachable doors and aftermarket Braje grille to finish 1st in Class H Modified at the 1952 International Sports Car Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. Note how the stock front wheel openings were enlarged.

Dolph Vilardi drove a yellow 1950 Hotshot #4 with optional detachable doors and aftermarket Braje grille to finish 1st in Class H Modified at the 1952 International Sports Car Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. Note how the stock front wheel openings were enlarged.

For the Crosley Hotshot LeMans Special, Dreyer acquired speed equipment from various sources, including Braje, Harmon & Collins, Iskenderian, Sun, and Bell Auto Parts, to boost horsepower from 26.5 to 42. Holes were punched in the hood to facilitate two chrome-plated intake stacks that allowed the down-draft carburetors to breathe. Powel Crosley was so enthused with the project that his boat trailer was modified to carry the newborn race car to the Pennsylvania Turnpike, where the vehicle was unloaded near Harrisburg, and George Schrafft climbed aboard. The Hotshot Special then roared off down the Turnpike in an attempt to break in the engine before being shipped to France aboard the S.S. Liberte.

Upon arrival at race headquarters, the crew discovered that the headlights were dim, so a French Marchal generator was installed. Road tests also revealed that a larger capacity gasoline tank was needed. Generous assistance came from the famous Cunningham racing team. The Hotshot LeMans Special performed well on race day, averaging 73 miles per hour on initial laps with plenty of power to spare. When cornering, the Crosley actually passed some competitors, including a Talbot, one of which won the previous year’s event.

Phil Stiles was pleased and a bit smug with the car’s surprising performance until the generator seized and a fire broke out in the cockpit. Choking on the smoke and unable to see, Stiles veered into the pits where the crew awaited fire extinguishers. The bearings in the replacement generator had failed. Because the fan belt also powered the water pump, cooling water could not circulate from the radiator into the engine. Stiles feverishly snipped away at the burnt wires and rerouted the water hoses to bypass the pump. He would rely on the old thermosyphon cooling method that had worked so well for American Austin and Bantam. In short order, the Crosley was back on the track. Unfortunately, the radiator was too small to cool the water, and the engine overheated. The Crosley Hotshot LeMans Special was withdrawn after completing only 40 laps.

Legendary race car builder Floyd “Pop” Dreyer built this custom Hotshot for Powel Crosley, Jr. Although its performance at LeMans was impressive, it was too late to save Crosley Motors.

Unfortunately, Powel Crosley’s promising premiere on the racing scene came too little, too late. He had invested heavily in his dream of building an auto manufacturing empire—$3.2 million of his own money, countless hours, and the sacrifice of his family life. But his best intentions could not win over a public that had no interest in tiny sports and economy cars. “The people in this country who go in for keeping up with the Joneses will buy a secondhand, beaten-up wreck rather than a brand-new small Crosley—if the big car still looks impressive to them,” he lamented. Crosley reluctantly closed the Company, and production officially ended on July 16, 1952.

Robert D. (Bob) Cunningham is a commercial illustrator and author of several automotive history books.

Robert,

Thanks for another great article, this one “Crosley Hotshot: Serious Contender Too Few Took Seriously.”

In the lead picture, behind the ’50 Hotshot, is a two-door 1941 FORD Sedan.

AML

Wonderful that The Old Motor has returned!!…hoping all went at least semi-smoothly.

In the Lead Photo, I see a ’41 Ford Super De Luxe Tudor Sedan , a couple of late-‘30’s Chevys and a ’38 Ford De Luxe Fordor facing us from across the intersection.

I recall that before I turned four after my parents bought our house,, I was finally tall enough to peer over the windowsill in the dining room of our Fair Oaks Apartment at 25th and Clinton in Minneapolis to see the regular morning passage of a Crosley wagon…before that, unless my Dad held me up to see out, I could only hear its distinctive burbling percolator-sound go past. Now I was thrilled that, without any assistance, I could enjoy my morning routine, complete with sound and a view of “my” Crosley…it sure was terrific to now be so grown up!

Welcome back David and The Old Motor. Glad you’re retooled and back rolling with another great story thanks to Robert. Hats off to the great yeoman’s work you do to keep this site tooling along. Happy Hump Day, woot woo.

Nice to have you up and running and back in action again and with another great article. I never knew that the Crosley Hot Shot was considered to be America’s first sports car, as I was under the impression that it was the Nash-Healey which was introduced two years later in 1951, although as far as where it was built goes was actually more British than American. I guess that one could say that Nash holds the distinction of being the first major American automaker to introduce a true sports car, although it was not mass-produced like the Corvette was that came out a couple of years later. The Nash-Healey however was a lot faster than the Crosley Hot Shot whose top speed was clocked at only 77mph on its small four cylinder engine. The Nash-Healey on the other hand had a top speed measured at 125 mph, just one mph less than the fabulous Hudson Hornet – the fastest car on the road at the time. Anyways, in the first picture behind the Hot Shot appears to be a 1941 Ford. And in the background behind the Ford parked on the street is that a 1938 Hudson Terraplane? Could be from what I can see of it.

The car in the background facing the camera is not a 1938 Hudson Terraplane as I conjectured but rather a 1938 Ford as Pat W correctly stated – I thank him for the correct ID.

Yes, the Nash was the first from a major manufacturer, but was after minors like Crosley, Kurtis (142.515 mph with a Ford V-8 at Bonneville in 1949, 104.6 mph with a Studebaker Six on roads, but only double digits sold), and arguably Muntz. Conversely, there were far more Hotshots than Nash-Healeys – 2,498 Hotshots produced to only 506 Nash-Healey (Crosley produced more Hotshots in 1949 than the total number of Nash-Healeys produced).

Well! I guess the system overhaul was a success. First story out of the gate is impressive!

Glad to see The Old Motor back online after the “tune up’. You’ve started off with a bang with another fascinating article and photos by Bob Cunningham. The detailed history fills in a lot of missing info on this remarkable little car.

I began driving in 1955, and would have given a lot for a chance to drive a Hotshot of any trim. Unfortunately Crosley had ceased production a few years earlier, and any Crosley on the street was rare, and I can only recall seeing one or two Hotshots. Thanks for the best site on the internet.

Good retro pictures and story. In the first photo it appears he may have a leaking axle seal or brake cylinder.

Thank you, Mr. G.

I know it’s not auto related, but it might not be amiss to mention Powell Crosley’s work in radio – it’s quite impressive, and created the cash which made the cars possible.

Bill

My favorite radio from my youth was my very own Crosley Fiver. Great small table model. With external antenna, WABC New York came in almost static free even here in North Ga. A clear channel station fun to listen to late at night was WWL New Orleans. Band leader Leon Kellner’s live broadcast from the Blue Room of the Roosevelt Hotel came on most week nights during the early-mid 60s. Thanks, Bill, for mentioning Crosley radios.

Great article.

I own a 49 Hotshot with the Brajevich add ones.

Great rig but still need to upgrade from the old downdraft Tilotson carbs and crude linkage.

BTW, I believe it is Nick Brajevich rather than Mick.

Ah, another article about a car which was many a boy’s dream, including me. Welcome back, David, it was a long, cold week without the warmth that The Old Motor brings to brighten my day. Floyd “Pop” Dryer whose contribution to the Hot Shot is highlighted in today’s story was also a notable motorcycle racer in his early days. There are a variety of articles about him which you can find if you google his name. I was honored to sit on the board of directors of the AMA (American Motorcycle Association) Heritage Museum which inducted “Pop” Dryer into it’s Hall of Fame but even better was my opportunity a number of years ago to sit in the sidecar of Mr. Dryer’s Indian race at one of the AMCA’s (Antique Motorcycle Club of America) annual meets in Davenport, Iowa. The dusty, midwest fairgrounds with it’s rough, dirt track which hosts vintage motorcycle races at its Labor Day meet each year was the perfect backdrop for Floyd’s old Indian racer. As I sat in “Pop’s” old wooden sidecar, I closed my eyes for a moment and was carried back to the early days when Floyd careened that same Indian along with its sidecar around that very track. If you google Floyd “Pop” Dryer, you’ll read about his post-motorcycle racing career at Indy, too.

We are happy to be back in cyberspace after the shutdown, thanks to all of you for the kind words about The Old Motor.

I love the photos of Dolph Vilardi’s Hotshot — although it may be a 1950 Super Sports. (The 1950 Super Sports still had the cutaway doors that usually identify a Hotshot. I think the only differences were the cockpit trim and the name plate.)

I also appreciate his windscreen. While most of us are running around looking for “period correct” Brooklands screens, Dolph is using an aftermarket MG wing window — mounted on its side in front of him.

1950 was the lone year for the Super HotShot, which was renamed Super Sports in 1951. Other than the trim and nameplate, there’s one other difference – the Super HotShot had a folding top instead of a stowed top. The Super Sports added hinged doors and switched to drum brakes instead of discs.

Thanks for raising the question about the standard Hotshot vs. the Super version. You’re touching on a nuance that Crosley aficionados know about, but few others do. When captioning the photographs, I looked for clues to determine whether Vilardi’s car was a standard Hotshot or the upgraded Super. The first place to look is the cowl script (Hotshot vs Super). Unfortunately, Vilardi removed his script. The second place is the cowl edging. Hotshot used a narrow edging while Super used a wide edging. Vilardi’s material is narrow. Lastly, the Hotshot top irons disassemble and stow behind the seat, while the Super top irons fold down over the rear deck. Vilardi’s fabric top material appears to be rolled, matching the Hotshot on the showroom floor in the upper left quadrant of the photo. The final point of reference was to compare the car with the fully restored 1950 Super version of the Hotshot in my father’s garage. All the evidence appears indicates Vilardi’s car was a standard Hotshot. By the way, Crosley never marketed the Super version of the Hotshot as a Super Hotshot. It was called a Super Sports from the start. Super Hotshot is a modern term used by Crosley owners to differentiate the 1950 Super Sports with its scalloped cockpit opening and detachable doors from the 1951-52 Super Sports with full-length flush doors.

I stand corrected, and in poking around I found a 1950 advertisement based on the Grand Prix de la Suisse Occidentale. It mentions the Super Sports “now with folding top, zipper side curtains, complete plastic leather cockpit edge trim,” so the company was using the Super Sports name in 1950.

It’s been decades, but I remember seeing a tiny dragster powered by a hot rodded Crosley Hot Shot motor at a vintage drag racing event that did pretty well.

Welcome back, David.

I had heard the Hotshot described as the first American postwar sports car before, but I hadn’t realized what a racing contender it was. I love the story of a dead-stock, borrowed Hotshot winning the Sebring race.

Glad to see The Old Motor back online, welcome back again.

jan

Excellent story about a pioneering American sports car.

Not mentioned (unless I read too quickly) were its early disc brakes and in one version a water-injection system (Vitameter) to permit its 10:1 compression ratio.

Phenomenal index win at Sebring. My only like with it is ownership of a Maserati later owned and driven by Koster.

Well, Mr. Ludvigsen, I find myself in August company being a poster on The Old Motor. Thank you!

That was meant to be “august” company. Mr. Ludvigsen is one of the best-known auto journalists. I am delighted to be in such company.

Comment forlorn viewers are eager to return, regardless of the post. Crosley’s always get attention. It was such an odd offering in a sea of barges. Just wrong timing and an interesting tidbit, unless mentioned, Crosley was the leader in radios, yet the Crosley car never had one. They used Motorola instead. Also, I believe Crosley touted the use of hydraulic brakes, 1st to offer disc up front, I believe, but as you can see in the 1st photo with LR leaking,, they were still in their infancy. 100 mph in this? That,, my friends, is nuts!

I was scared just to read about doing 100mph in a Crosley. The suspension must have been fairly good. And no better story than to borrow a road car making a delivery to win a race. And good to see (read) you Howard.

Automobile Club de l’Ouest, rather than Quest?

Our family had two Crosleys. There is a treasured photo of my two oldest brothers staring into the engine compartment of dad’s Crosley station wagon in the late ‘40s. They went on to be hot rodders in the years ahead. And another large photo shows us kids and some cousins sitting and standing around a Hotshot. Didn’t even know what it was called until a few years back, when I found the damaged owners manual in my dad’s stuff. Memories!

Interesting looking Crosley Special in the final picture. It looks like Allard decided to make a 1/4 midget.

Not sure if you read the article? That’s not a ‘special’ – it’s the official Crosley factory entry for the 1951 Le Mans.

Welcome back!

Thanks Mike!

Really nice write up – and you got the details right (a real rarity in any reporting on Crosleys.) Would love to know more details on the 1950 Grand Prix de la Suisse Occidentale – there was a nice looking Crosley-based 500 cc special called the Este 500 shown in Switzerland at about the same time… I’ve never been able to track down any details, like how the Crosley motor ended up in Switzerland and why was it sleeved down to 500cc? Makes me wonder if Feierabend or Bernasconi were involved. Anyway, nice work!

If the Auto Puzzles poster mentioned in your May 7, 2020 post is correct that it was an F3 car, sleeving it down was to meet category requirements. Formula Three had a 500 cc displacement cap in 1950, which I don’t believe was increased until 1964. Crosmobile imported into Switzerland, so the motor may have been pulled from an imported vehicle.

The Swiss group wasn’t the only race car manufacturer using Crosley engines, since Ilario Bandini used them starting in 1950 for his 750 cc sport siluro, originally lightly modified ones producing 45 horsepower at 7200 rpm and later extreme rebuilds producing 71 horsepower at 8100 rpm.

Bob, thanks for a great article. The PA turnpike was used to break-in the engine. When the PA turnpike was brand new, 1945, and for some years thereafter, it was an unlimited speed road, much like the sutobahns of Germany. Government soon learned that it made more sense to control speeds and make money on lawbreakers. Somewhere in the early 50’s, they put a speed limit on the road.

The PA turnpike had no speed limit (except for the tunnels) from when the first section opened (October 1, 1940) until April 1941, when a 70 mph limit was instituted for cars and 50-65 mph for trucks. During World War 2, it had the nation-wide speed limit of 35 mph. It was restored after the war and reduced to 65/50 for cars/trucks in 1956. Changes since then have been due to changes in national law.

I have a 1950 Hotshot with a “Bearcat” motor. Complete Braje equipment and my custom dual exhaust. Brooklands wind screens. A hoot to drive on PCH here in So. Cal. More looks than any other car I’ve owned.

Thanks for a great article. Some corrections, remarks and thoughts on the Swiss racing with Crosleys (or rather Crosmobiles). First, according to what I have read, it was Fritz Feierabend and Jean Wagner who had compressors (Ital-Meccanica), and Oviero Bernasconi’s car was “stock”. Second, I belive the race was acutally called Grand Prix de Thurgovie (Preis der Thurgau), Grand Prix automobile de Suisse orientale (Preis der Ost-Schweiz) was the main event for F2 cars. Third, yes the Crosmobiles ended up winning, taking second place and even third – BUT it was only three cars entered, all Crosmobiles…

Ecurie Crosmobile (the Swiss team) entered cars in several other races with limited success (German Grand Prix, Rallye des Neiges, Susa-Moncenisio and others).

Best regards from Sweden